What is GPR in the Self Storage Industry?

Gross Potential Revenue (GPR) is a widely used metric for self-storage real estate investment decisions. While it can be helpful for investment decisions, when it comes to tactical pricing decisions, it is often misused and has led to pricing mistakes by some operators.

GPR provides a facility’s (or portfolio’s) potential monthly or yearly revenue estimate that a self-storage operator or investor can expect. For a facility in lease-up mode, GPR can provide valuable estimates to support financing decisions. However, for a mature facility, using GPR to guide pricing decisions can often lead to reduced revenues and profits. Let’s review why.

How do you calculate GPR?

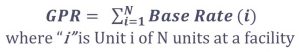

In a self-storage facility, each self-storage unit has a “standard” or “base” rate. This rate represents the potential rent a unit can bring for the given time period. GPR is the sum of all these units’ rents across the entire facility. For the more mathematically inclined:

It is important to note that GPR assumes 100% occupancy. Together with each unit’s rate, GPR provides an estimate of the overall facility’s potential revenue.

For example, let’s say a self-storage facility has 100 units. For simplicity, assume all units are the same and all have a potential rent of $95 per month rent. Because GPR assumes 100% occupancy, the monthly GPR would be $9,500.

A self-storage investor might then look at other nearby facilities to gauge market rents accuracy and assess whether the estimated GPR is reasonable. The investor can use this information to evaluate a store’s potential profitability. He or she can then decide whether the store qualifies as a good investment. The investor can then use GPR to help determine the appropriate levels of investment and loans to make.

Since GPR represents a facility’s potential to generate revenue, it might seem GPR should also be used as a benchmark for pricing decisions. After all, wouldn’t prices that result in a greater GPR imply higher potential revenues. And, by extension, shouldn’t appropriately set prices result in higher GPR’s as occupancy increases?

The answer is not as obvious as you might think.

In the real world, rents (should) fluctuate based on market demand. But GPR is not reflective of this demand.

Many self-storage facilities experience softened demand towards the end of August through the winter. To maximize revenues, and therefore profit, the smart approach is often to anticipate the lower demand and reduce rates in mid-August: Even when mid-August occupancies are higher than end-of-winter occupancies!

That is, it can be most profitable to begin reducing prices before existing occupancy actually drops. In short, you are proactively preparing for the winter months, rather than reactively responding.

However, if you measure against GPR, you will find that when you reduce your prices, you are lowering your GPR. For many operators, lowering your GPR when occupancies are at their highest seems like a mistake. But it can be exactly the right decision to make to maximize profit!

The higher prices that were justified in June and July, as occupancy was building, are no longer justified and supported by the market. Keep your prices high to maintain GPR, or even worse, increase your prices in mid-August to increase GPR because your occupancy is higher now compared to several months earlier, and you may be in for a very rough winter. Sure, your GPR is strong, but you don’t take GPR to the bank; and you’ll likely be taking less revenue to the bank.

Yes, there are times when raising rates in mid-August is the most profitable course of action to take even when demand is declining. Yes, there are exceptions to the guidance provided above. But, as a general rule, reducing rates when demand is softening, even if it reduces your GPR at high occupancies, will yield greater revenues and profits.

In a future blog, we will provide a simple math example that illustrates just how this happens.

GPR underestimates revenue potential when Value Pricing is in play.

More recently, due to the success of Value Pricing, GPR can be even more misleading when used as a guide for pricing, and quite likely, even for investment decisions. Value Pricing, also known as Differentiated Pricing, or “Good”–”Better”–”Best” Pricing, provides customers with an opportunity to pay more for otherwise similar units that offer more convenience, such as better accessibility, even though the size and climate control is the same. But it does so dynamically behind the scenes, without creating additional unit groups!

For companies using Value Pricing, the average move-in rent is greater than the base or “street” rate (essentially, the asking rate). GPR simply does not capture this dynamic. And with upgrade rates of 40 – 60 percent in lease-up facilities, GPR will significantly underestimate a store’s potential revenue. While you can adjust GPR to reflect this dynamic, few companies think of doing so. Or, accounting report limitations might also constrain companies.

As the industry evolves, leading companies have recognized that there are new and better metrics and procedures available for price setting. Our guidance: make sure you are on board the Pricing Train! You do n0t want to be left behind at the station.

Special thanks to co-author Kevin Bowman, Managing Director, Revenue Management at StorageMart. Based in Columbia, MO, StorageMart operates over 200 facilities in the US, Canada, and UK.